This past month I spent 11 days at the Northfield campus of Mt. Hermon Northfield School where we held our annual winter residency for the New England College MFA Program in Poetry that I co-direct. Being in Northfield, MA after nearly 30 years brought back many memories. Little has changed since I went to high school there graduating in 1968. It seems that even the cracks in the road were the same. My first husband, Stephen Warren Curtis, was born and raised in Northfield. I recently came across a website (click on the title) with his art work that my brother, Will, forwarded to me. Being on that abandoned campus, one of our faculty called, a “Wuthering Heights” experience (Steven’s favorite book), brought me back to my late teens and how formative those years were.

I was married to Stephen Curtis from 1969-1971 or 1972 (legally until 1982).Here I am in a photo booth shot the year I met Steven looking a bit like Madame Blavatsky. All of the works on this website by Steven were executed during the time we lived together in Bernardston, Massachusetts which subsequently were incorporated into an offset pamphlet that Stephen created. For years I would find the pamphlet in odd places such as in a storefront window in Harvard Square. I recently heard from Clayton Campbell that when John D. Merriam (Stephen’s primary collector) died his collections went to the Wiggins collection in Boston.

Both my grandparents were visual artists by profession and so marrying an artist seemed an obvious choice. Stephen and I were very inexperienced in terms of relationship, so things were always on shaky ground. I was 19 and he was 24 when we married in April of 1969, Originally, I had just wanted to run off to Boston with him but my mother pressed us into getting married and moving in with her as she liked Stephen quite a bit. In the end, that proved counteractive to my own desires to leave home and get out into the world. On the other hand, things happen for a reason, and this period of my life, while extremely difficult, proved rich inwardly setting in motion the direction I’m still uncovering today at age 57, decades later.

Like many of his friends, what I most enjoyed about Stephen was his integrity and total dedication to his art, as well as his quirky sense of humor, I was not surprised when I heard that he was found dead sitting up in a chair with a book opened on his lap to Ingress, a lifetime influence of his. While we were married, a local doctor whom he had once consulted, Dr. Failla, told him he would be dead at the age of 54 of a heart attack unless he changed his diet and lifestyle. I had heard that he tried to do this in his later years but I doubt he ever made it to the gym. By nature he was sedentary and genetically probably disposed toward high cholesterol. His family was poor and he grew up on comfort foods from the get go, — primarily of the white kind—wonder bread, potatoes. On the other hand, it seems that he died peacefully gazing on his most beloved vision of perfection.

Like Stephen, I had gone to Pioneer Valley Regional High School

In Northfield, MA when my family moved to Bernardston, MA in my senior year. His class would have been about 4 or 5 years earlier than mine. Prior to then, we had lived in Southern California and New York City. Our cultural backgrounds were totally different—mine first generation, eastern European and French, Catholic—his, generations of New England hardscrabble.

But Stephen had his guardian angels growing up—mainly the lively St. Clair clan of 88 Main Street Northfield who shared their somewhat magical family life with him supporting his artistic talents throughout his youth. One of the few changes I found on Main Street in Northfield was that the old rambling mansion of 88 Main had been replaced by a modest housing unit. Many of Stephen’s works were inspired by his muse, Eva (who later married the artist, James Langlois), one of the beautiful St Clair sisters, who can be seen in some of the drawings featured on the website.

Nonetheless, we had a lot in common on the psychic level as both of us lived in the shadow of early childhood iconic influences and family dysfunctions (a word not much in use back then). Yet, both of us we able to discuss serious issues like sexual abuse and homosexuality, at a time when there was little public discourse happening about these rather taboo topics. That is another aspect of my relationship with Steven that I appreciated. From Stephen, I primarily learned to draw on this energy for artistic sustenance rather than rejecting it as shameful or an unwanted intrusion, He also introduced me to many writers although I was fairly well read by the time I had met him. While married to him, I read the entire works of Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, and Eric Neumann whose works enriched my interests in anthropology and comparative religion eventually bring me to Tibetan Buddhism. One present he gave me was the complete works of Ezra Pound. These authors probably came to him via Yglesias, a popular professor of comparative literature at Brandeis, about 10 years his senior and a great influence on Stephen intellectually and later for me too.

So in retrospect, I’m very happy that I married Stephen because through him I learned a lot about the creative process and the unfolding of my deeply intuitive nature that I had tried to suppress throughout my childhood. On the practical level, we kept very different schedules. He would work all night until about 5:00 AM in the morning while I would sleep. I supported him and my family to some extent by working the second shift at a plastics factory. Back in 1971, it was still possible to feed an entire family of six for a week on $25 worth of groceries. I earned about $60 a week. As my family tended to be somewhat bohemian, this worked well for a while but after some time I found the regiment of factory work boring and unfulfilling for me personally. But it never ceased to amaze me when I would check in to his studio the next day after he had gone to bed, that he had worked hours on rendering some small detail of a drawing to perfection whether of a head of romaine lettuce or some fantastical being not of this realm. Many of his works started up as murky sketches, messes really, that would become jewels of crystalline clarity through his use of plain graphite on paper.

Unlike Stephen and his circle of male artist friends (Jimmy-Joe Langlois, Mark Spencer, Clayton Campbell, his mentor Luis Yglesias), I had not gone to College, nor had anyone in my family. In the mid-seventies after Steven and I separated, I would return to school eventually earning my BA in classics from Smith which I attended from 1978-1981 as one of the first Ada Comstock Scholars—waitressing and bartending my way through school while hitch hiking to class from Packer Corners Farm where I then lived.

Following my graduation, I legally divorced Stephen who was living in Boston since I was planning to move to Boulder, Colorado to pursue my interests in Tibetan Buddhism and language at the Naropa Institute. By then we had little contact or shared interests although we usually stayed in touch by phone every couple of years. In 1998, while working on a conservation job at the state capital in Madison, Wisconsin, I tried to call Stephen. But his number was disconnected. I then left a message on Beatrice St. Clair’s phone asking about him. Beth Backman (nee St. Clair) kindly returned my phone call to let me know that Steven had died a couple of years before. I eventually visited her a few times to catch up on Stephen’s life.

A lot of my journey does not include Stephen as I went on to live a few years at Packer Corners Farm (Total Loss Farm, his then friend Luis dubbed it), an altogether other story, then on to Boulder for 7 years where I worked at Naropa Institute in the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, on to NYC for another five years to work for the poet, Allen Ginsberg, then back here to New England where I’ve been in Brattleboro, Vermont since 1995. For the past 25 years I’ve been a student of Tibetan Buddhism primarily of Chogyam Trungpa’s (1939-1987) Shambhala lineage and the Dzogchen lineage of Choegyal NamkhaiNorbu.

On a rare note of curiosity one day, the poet Allen Ginsberg once asked me when I visited him at Lenox Hospital (circa 1987 when he had his gall bladder removed) about my early influences. Across from his bed was a reproduction of the girl with a watering can by Degas. I flashed on living with Steven nearly two decades earlier where once I had made a collage out of the girl with a watering can by meticulously cutting out a picture of Bob Dylan’s head and superimposing it on the Degas image that hung in our dining room for years. At the moment, Allen was thrilled with a hugely lush bouquet delivered to his room he had just received from Dylan’s office. “I took the left hand road” I told Allen that day, ” and never regretted it”. “Me too” Allen said. The day I married Stephen was the day that I took that decisive turn in the road and it led me to where I wanted to go.

At the heart of Stephen’ s work and his colleagues in the school of mystical surrealism, is a plumbing for unconscious artifacts emerging into the light of ordinary consciousness. In Steven’s case, there was the paradisiacal return to childhood images found in the Northfield landscape lived in the shadows of Moody’s progressive edifices with its elegant landscape and raw from his family dynamics who worked as servants on the Moody estate for generations. As such, the circumstances of Steven’s birth and his pedigree provided the classic ingredients for a “wounding” into artistic presence. As a poet many of the writers I admire come from such backgrounds, growing up out of the swamp, the backwoods, the ruined portal of passage from the lowest social strata to the higher realms of a pure perception through their art.

Although Stephen’s mother, Leolyn Curtis, who had conceived him out of wedlock in the 1940’s always claimed to him that he was the son of her love interest, a prosperous local farmer who had many children, it was widely known within the town that Steven’s actual biological father was an eccentric painter who lived with his mother from one of Northfield’s leading patrician families. Apparently, not only did Steven inherit his father’s artistic talent he exhibited at an early age but his looks as well.

This mixed message considerably shaped his artistic vision in that his work explores the classic surreal ethos that things are not what they seem. Within the sometimes harsh and violent imagery of his work can be found a tenderness, the sadness of Eros or what William Carlos Williams came to call “Unworldly love that can not be satisfied. Like numerous artists before him, he circled this justification of art to make up for life’s impossible dilemmas that can be found in the arcane imagery of the Northfield chateau as a citadel of sanity and home to his erotic interests whether male, female or hermaphroditic who often appear in the guise of mythological figures.

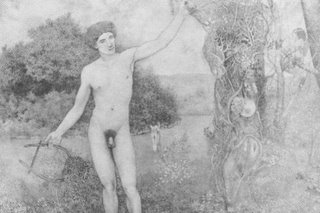

Here is Apollo with his lyre lingering at the tree of Daphne transformed into a rich tangle of foliage, the real lovers embracing in the background in the Connecticut river, the entire scene transposed to Northfield, Apollo’s heart forever broken in unrequited love with an impossible yearning.

I don’t know much about Stephen’s life after the 1980’s except that he worked as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art where I’m sure he engaged in all sorts of conversations with aspiring artists.He was a great raconteur.

In many ways, Stephen’s lifetime achievement was his actual artistic process. It doesn’t matter that he did not become famous or ever have a major show although he certainly deserved some kind of show along with his colleagues. He lived the archetype of the quintessential artist forever beholden to his inner vision to render into worldly terms images that transcend into universal ciphers of tender unworldly love.