Reading "By and Large", by Philip Whalen in Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1987

part one (31:48): MP3

This sound recordings is made available for noncommercial and educational use only. All rights to this recorded material belong to Philip Whalen © 2004-2007. Used with permission of the Literary Estate of Philip Whalen. Distributed by PennSound.

CLICK ON THE TITLE to hear.

For Philip Whalen historic reading at the Vancouver Poetry Festival, University of British Columbia, July 31, 1963 complete reading (1:12:45): MP3 click here.

Joanne Kyger reading, introduced by Robert Hass at University of California, Berkeley

The video is about 30 minutes long and well worth watching.

Saturday, December 29, 2007

Friday, December 28, 2007

LA Times Reviews Philip Whalen's Collected and Joanne Kyger's About Now

"Whalen and Kyger are essentially School of Backyard poets, who look out their kitchen windows and see the universe. Both have given themselves permission to write about what is immediately in front of them and/or on their minds, no matter how exalted or mundane. They are both domestics who leave plenty of room for splendor. Both have mastered the conversational; both feed off slang. Everything is the subject of their poems. Now, these two remarkable careers are represented by a pair of retrospective collections: "The Collected Poems of Philip Whalen," edited by Michael Rothenberg, and Kyger's "About Now: Collected Poems."

"Whalen and Kyger are essentially School of Backyard poets, who look out their kitchen windows and see the universe. Both have given themselves permission to write about what is immediately in front of them and/or on their minds, no matter how exalted or mundane. They are both domestics who leave plenty of room for splendor. Both have mastered the conversational; both feed off slang. Everything is the subject of their poems. Now, these two remarkable careers are represented by a pair of retrospective collections: "The Collected Poems of Philip Whalen," edited by Michael Rothenberg, and Kyger's "About Now: Collected Poems."To read more of Lewis MacAdams' fine review, click on the title above.

A few online resources:

Philip Whalen Archive Bancroft Library Berkeley

Electronic Poetry Resource links on Philip Whalen (the most comprehensive)

Randy Roark's Essay on Philip Whalen

"What do I know or care about life and death My concern is to arrange immediate BREAKTHROUGH into this heaven where we live as music" Philip Whalen

from an email I wrote following Philip's death in 2002.

Dear Friends--fellow poets and meditators:

Poet and Zen master, Philip Whalen, Roshi died on June 26 (2002) at 5:50 am. Among the last of the surviving beat generation writers, Philip was a remarkable and authentic presence. I count him among my first dharma teachers. He was a friend and teacher to many Buddhists from all the practicing lineages.As a poet, he was uncompromising in his dedication to remain true to his calling, outside the range of conventional literary circuits--so rare these days.

On October 6, 1955, he was a participant in the historical Six Gallery reading in San Francisco where he read with Kerouac, Ginsberg, Snyder, Philip Lamantia, and Michael McClure. His poetry appeared in issues of the Evergreen Review, as well as other small journals of the period, and in 1960 he appeared in Donald Allen's New American Poetry anthology. Whalen is the author of numerous books of poetry, including Like I Say and Memoirs of an Interglacial Age which, along with other early books, were collected in the 1967 publication of On Bear's Head. He is also the author of two novels, You Didn't Even Try and Imaginary Speeches for a Brazen Head. More recent books include The Kindness of Strangers, Severance Pay, Scenes

of Life at the Capital and Canoeing Up Cabarga Creek.

Throughout the 1970's and 80's he taught at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied poets at the Naropa Institute (now university) where I had the privilege of living with him and Allen Ginsberg the summer of 1985. I owe a lot to him for breaking through my ignorance about the 'nature of mind.' An imposing presence and mountain of a man, he could stop your mind with a gaze.

Not one actively to seek fame, in fact, outright rejecting its lure at the height of the San Francisco poetry renaissance and his own burgeoning career, Philip was among the first generation Americans to fully embrace the Buddhist teachings living for many years in Japan

while studying with traditional Zen masters before returning to the US where he spent the last 30 years or so devoted to his practice primarily-- then some on his poetry. In recent years,

although nearly blind and in failing health, he was installed as Abbot of the Hartford Street Zen Center in San Francisco, a hospice dedicated to working with Aids patients. His life's work embodied the classic paradigm of the monk/poet living simply and with great impartial compassion towards all.

Warm Regards, Jacqueline Gens

Japanese Tea Garden Golden Gate Park in Spring

1.

I come to look at the cherryblossom

for the last time

2.

Look up through flower branching Deva world

(happy ignorance)

3.

These blossoms will be gone in a week

I'll be gone long before.

an excerpt 2:iv:65

Philip Whalen 1923-2002

Monday, December 24, 2007

Solstice Greetings 2007

Solstice Greetings 2007

Tip north, darkest day of the season

but down below, reverses to the longest

with sunny rays dead on.

Either way, when gaiety dons

festoons of snowy boughs or fruit laden

arbors heaving to golden harvests,

our work is done as we anticipate

the New Year, between the dark

and light of solstice.

You hoary voyagers—my friends

bearing gifts of luminous mind

outside the turn of celestial events,

I send you greetings

from north to south

across the equatorial circumference

of our common purpose,

whose light, after all,

outshines the arc of time.

*Nasa composite image of the sun using extreme ultraviolet light at summer solstice circa 2004 from different vantages on earth.

Sunday, November 11, 2007

Louise Landes Levi to Read in Brattleboro, VT on December 8, 2007

I recently caught up with poet, LOUISE LANDES LEVI, in Italy where she lives in a tower located in the hill-top village of Bagnore, on the slopes of Mt. Amiata, Tuscany, the highest mountain in Tuscany. Here she writes, tutors students in poetics and music, performs

I recently caught up with poet, LOUISE LANDES LEVI, in Italy where she lives in a tower located in the hill-top village of Bagnore, on the slopes of Mt. Amiata, Tuscany, the highest mountain in Tuscany. Here she writes, tutors students in poetics and music, performslocally in the cafes and writes. She sells books locally & to practitioners who come to study with Choegyal Namkhai Norbu, a Tibetan Dzogchen master, from points as far away as Japan & New Zealand, and to the international body of practitioners who travel to the area.

Both Louise and I were attending a retreat taught by Choegyal Namkhai Norbu, with whom we’ve studied with for many years. Each day after the teachings, Louise would take me on a tour of the local region surrounding Mt.Amiata.

Here’s the visitor sign to Merigar where our retreat was held on the small road heading about 2 km uphill into a nature preserve on the slopes of Amiata where it appeared to be wild boar hunting season with blackberries in bloom all along the roadside. Merigar is located at the tip of this hill with views of farms and hay fields. Louise walks these roads between the complex of hill top villages in this rural part of Tuscany on ancient pathways as old as the Etruscans. Across from Merigar is a small mountain called Mt. LABRO, a mercurial mountain, where a prophet-- Catholic anarchist David Laszeretti, predicted the arrival of an 'oriental' teacher, some 100 years after his passing. Laszeretti was murdered by local police called in Italian, Carabinieri. Here, the 19th century visionary lived in an underground tomb of an Etruscan king. The entire region is a volcano with numerous sulphur springs that have been used medicinally since the time of the Romans.

Louise took me to such interesting sites such as Daniel Spoerri's extraordinary sculpture garden on his estate in Seggiano, the 12/13th century cave of St. Philippe and several local "poets" houses in the towns where they were remembered with a bronze markers-- all the while talking of poetry and dharma.

After many years of hearing about it or receiving post cards from her while living in her tower, I was finally able to visit it in person.

After many years of hearing about it or receiving post cards from her while living in her tower, I was finally able to visit it in person.Louise will read at the Hooker-Duhnam Theater on Main Street in Brattleboro, VT on December 8, 2007 at 7:00 PM.

For further information and details go to the blogger link for the Brattleboro Center for Literary Arts.

International poet, classical sarangi musician, scholar, and translator of Rene Daumal and Henri Michaux, Louise Landes Levi has traveled the globe for three decades. Her poetry books include, Banana Baby (Supernova, 2006), Avenue A & 9th Street (Shivastan, 2004), Chorma (Porto dei Santi, 2000) Guru Punk, (Cool Grove Press, 1999), Sweet on my Lips, Love poems of Mira Bai (Cool Grove Press, 1997), The House Lamps Have Been Lit (Supernova, 1996), Extinctions, (Left Hand Books, 1993), and Concerto, (City Lights, Accordian Series, 1988). Rene Daumal’s Rasa was published by New Directions in 1982 and most recently, Toward Totality (Vers La Completude) & Selected Works 1929-1973 of Henri Michaux (Shivastan, 2006) and Toward Totality I / Vers La Completude (Longhouse, 2006). Reviews, essays and poems have been published online in Big Bridge, Jacket, and Rain Taxi, among other publications.

Beatific Soul: Jack Kerouac On the Road at the New York Public Library

Beatific Soul: Jack Kerouac On the Road will show at the New York Public Library from November 9-February 24, 2008 and March 1-16, 2008. The show includes 60 feet of the On the Road scroll manuscript alomng with numerous images taken by Allen Ginsberg and holdings from the Kerouac archive.

Beatific Soul: Jack Kerouac On the Road will show at the New York Public Library from November 9-February 24, 2008 and March 1-16, 2008. The show includes 60 feet of the On the Road scroll manuscript alomng with numerous images taken by Allen Ginsberg and holdings from the Kerouac archive. The arrival of the 50th anniversary of Jack Kerouac's On the Road is an important moment in American letters for at least two reasons: first, because Kerouac (1922 –1969) is generally regarded as chief of the triumvirate comprising himself, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs, who were fathers of the Beat movement; and second, because the sensation caused by the publication of On the Road brought Kerouac to the attention of a national audience,” said Library President Paul LeClerc. “The New York Public Library could not allow this significant anniversary to pass without a significant exhibition and accompanying publication, especially since in 2001, the Library's Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature acquired the Jack Kerouac Archive.”

On the Road was inspired by four cross-country road trips taken by Kerouac, three from New York to California and back, and a round trip from New York to Mexico. Drafts, fragments, and journal entries show Kerouac's literary journey while writing the novel. The 1949 notebook “Night Notes,” which includes a hand-drawn map of the United States; the 1949-52 Rain and Rivers notebook, bearing the evocative subtitle, “The Marvelous notebook presented to me by Neal Cassady in San Francisco Which I have Crowded in Words”; the 1950 “Hip Generation,” and the 1950 fragmentary draft bearing the working title “Gone on the Road with Minor Artistic Corrections,” are among the revelatory journals, notebooks, and drafts that reveal the enormous amount of work and thought that Kerouac expended on the novel, and the daring with which he carried it out. A visual highlight displayed is a 1952 pencil and red pen drawing of Kerouac's design for a never-published paperback edition of On the Road; a man stands with his back to the reader, in front of a highway with the words “by John Kerouac Kerouac Kerouac Kerouac” cascading down the road like a speed warning. Photos and communication to, from, and by the other Beats are interspersed throughout the exhibition. Drawings and paintings by Kerouac are also featured, revealing the seriousness of his artistic ambition and the talent that justified it.

Wednesday, November 07, 2007

The Old, Weird America: Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music to Show at the Margaret Mead Film & Video Festival

Rani Singh's 90 minute film on the work of Harry Smith, The Old, Weird America: Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music will show at the American Museum of Natural History on November 10, 2007 at 8:15 PM

Every fan of American music owes a debt to Harry Smith. Driven by his unique sensibility and passion for authentic, offbeat music, he amassed an unparalleled collection of recordings and brought attention to numerous unrecognized artists. His musical legacy is celebrated here through archival footage, interviews, and filmed stage performances by a diverse group of artists, including Nick Cave, Percy Heath, Philip Glass, Kate and Anna McGarrigle, and Elvis Costello.

The Margaret Mead Film & Video Festival

Located at the American Museum of Natural History

Central Park West at 79th St.

New York, NY 10024

Phone: 212.769.5305

Fax: 212.769.5329

To read my blog entry on Harry, click here

Wednesday, October 31, 2007

Philip Whalen's Collected Forthcoming from Wesleyan University Press

The Collected Poems of Philip Whalen, edited by Michael Rothenberg of Big Bridge Press with a forward by Gary Snyder and introduction by Leslie Scalapino is due out in November 2007.

The Collected Poems of Philip Whalen, edited by Michael Rothenberg of Big Bridge Press with a forward by Gary Snyder and introduction by Leslie Scalapino is due out in November 2007. Review Forthcoming.

Sunday, October 21, 2007

Forthcoming Poetry Readings by Jacqueline Gens

Jacqueline Gens will read in Amherst, MA on November 2, 2007 for The Hampshire County Partnership to Improve end of Life Care program along with poets, Barbara Paparazzo and Christie Svane at:

How We Remember: A Day of the Dead Celebration

Friday, November 2, 2007 beginning at 7:30 pm

Nacul Center

592 Main StAmherst, MA

The festivities include

• an art show with the theme of remembering,

• A mariachi band to add to the celebration,

• Food and beverage (of course!)

• a program consisting of readings, dance and other

entertainment with the theme of remembering.

5:30 – 7:30 pm open art exhibit, live music

7:30 - 9:30 pm poetry program

The Partnership is a nonprofit organization with the mission of educating the community to make informed choices about end of life care. Because the Partnership recognizes that dying is a part of living, our goal in having the Day of the Dead weekend is to invite our community to take part in activities to help raise awareness of the issues surrounding death in our culture.

***

Putney, VT Library Series, December 6, 2007, Jacqueline Gens and John Rose of Landmark College will read. Further details TBA

Jacqueline Gens is co-director and a founder of of the MFA Program in Poetry at New England College. For many years, she worked for the late poet, Allen Ginsberg and is a long time practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism. Her manuscript, Primo Pensiero, with a foreword by Anne Waldman, is forthcoming from Shivastan Publications in the winter of 2008.

Saturday, October 20, 2007

Backstory

My poem in honor of the Dalai Lama receiving the Congressional medal of honor on November 17, 2007.

10/17/07

by Jacqueline Gens

Backstory

Above the din of Amy’s café

in the backroom overlooking the river

loud words drift over to our table,

Did the Dalai Lama ever have a job

like shinning shoes? The old Vermonter

leans towards his wife who's eating a croissant

looking away from him.

I want to reach across the room

and tell him “yes” about my dream

of the Dalai Lama in a glass airport tower

directing traffic on the runway

of life and death and that his question

isn’t so ridiculous as his wife’s response suggests.

I want to tell him that the monk once held my left hand

at a reception while he massaged my palm

looking into my eyes talking of nothing much

as he rearranged my subtle energies,

my right hand gripping

the glass of white wine until I jumped

in recognition of what was happening.

So strange, so intimate, so wonderous--

the shock of his kind gesture in passing,

as loud as the man’s words in the café.

10/17/07

by Jacqueline Gens

Monday, September 10, 2007

Barbara Moraff

Vermont poet, BARBARA MORAFF recently sent a letter regarding a project she is fundraising for in honor of her much loved son, Marco Moraff Alonzo, who died April 18, 2007. Although diagnosed with cystic fibrosis, Marco lived far beyond his normal life expectancy with a passion for painting, gardening, sculpture and writing. He taught organic gardening for youngsters at the White River Junction Community Gardens. Barbara is currently collecting funds for a three-stage composting facility for the White River Community Gardens in Marco's honor.

Vermont poet, BARBARA MORAFF recently sent a letter regarding a project she is fundraising for in honor of her much loved son, Marco Moraff Alonzo, who died April 18, 2007. Although diagnosed with cystic fibrosis, Marco lived far beyond his normal life expectancy with a passion for painting, gardening, sculpture and writing. He taught organic gardening for youngsters at the White River Junction Community Gardens. Barbara is currently collecting funds for a three-stage composting facility for the White River Community Gardens in Marco's honor.Donations can be mailed to:

Barbara Moraff

76 Harveys' Hollow Road

Danville, VT 05828

Click on her name above to link to her wikipedia biography and list of publishers and publications. A couple of summers ago while I cooked for a two week retreat at Karme Choling in Barnet, Vermont, l met Barbara again after 20 years when we first attended Chogyam Trungpa's last 3 month seminary retreat together back in 1986. She makes the most extraordinary Tibetan Barley Bread that she sells along with her pottery to supplement her income. Along with her recent letter, she sent a fine Longhouse limited edition book, Footprints.

Online poetry from Barbara Moraff

Three Poems for Cid Corman

Here's a great photo of Barbara and Allen Ginsberg circa 1959, I found on Kingdom Books blog [Allen Ginsberg and Barbara Moraff at 7 Arts Coffee Gallery, NYC, 1959; photo by Dave Heath]. You can also read more on Barbara on their site.

Wednesday, August 01, 2007

Robin Kornman (1947-2007) Translator of Gesar of Ling

Professor Robin Kornman, reknowned Tibetan translator and scholar of the Tibetan Gesar of Ling epic died peacefully on July 31 after a long illness. Robin was a life-long student of the late Tibetan master, Chogyam Trungpa, founder of Naropa University, whom he met in his youth. As a translator of Tibetan literature, Robin was part of the Nalanda translation team who worked on The Rain of Wisdom, one of the first collections of Tibetan poetry translated into English.

Professor Robin Kornman, reknowned Tibetan translator and scholar of the Tibetan Gesar of Ling epic died peacefully on July 31 after a long illness. Robin was a life-long student of the late Tibetan master, Chogyam Trungpa, founder of Naropa University, whom he met in his youth. As a translator of Tibetan literature, Robin was part of the Nalanda translation team who worked on The Rain of Wisdom, one of the first collections of Tibetan poetry translated into English.For decades Robin devoted his life to working on translating the

Gesar of Ling epic, the longest epic in world literature believed to be over 1000 years old and still widely performed through out Central Asia. While a number of translations exist of the Gesar epic, Robin's unique gift and exacting scholarship rivals many of these translations. For an exquisite taste of his elegant language, click here, to access some examples. The Gesar of Ling represents a living Heroic epic cycle where the forces of good and evil are played out in the human realm. In Robin's own words:

The Tibetan Epic of Gesar of Ling is an immense oral epic which is still sung by bards. It exists in literally hundreds of volumes, some of them transcriptions of bardic performances, others original compositions.

The Gesar is a vast treasury of Inner Asian literary culture. It is still sung today in Tibet and is known in different languages and editions along the Silk Route and throughout the Far East. It contains long sections of prose narration alternating with hundreds of epic ballads and examples of every sort of poetry in the Tibetan repertoire, both folk and classical. In size it is like The Arabian Nights. In its breadth, unity, and seriousness, it is like the Homeric epics or the Mahabharata.

It tells the story of a enlightened warrior named Gesar. At the beginning of the epic he is a Buddhist deity named Good News, living peaceably in a Buddhist heaven. The Tibetan tantric sorceror, Padmasambhava, and the bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteshvara, attempt to involve him in worldly affairs. These events are reported in the extremely metaphysical first volume of the epic, the Lha gLing or The Divine Land of Ling.

During the years I worked for the poet, Allen Ginsberg, Robin met with Allen on a number of occasions for feedback on his translations into English. For a fine article on Robin, read Larry Mermelstein's recollection.

Wednesday, July 25, 2007

Tibetan Poets Featured in Cutthroat Magazine

Two Tibetan activist/poets, Lhasang Tsering and Tenzin Tsundue, are featured in the current issue of Cutthroat Magazine, Vol. 3, Summer 2007 Issue. Click on the title above to access the online version.

For further links to Tenzin Tsundue's work, click here.

Both poets represent the movement toward an independent Tibet from exile. They are also featured in the anthology, Muses in Exile [ISBN : 81-86230-48-3 Publisher : Paljor Publications Pvt. Ltd], the first major anthology of contemporary Tibetan poets in English writing outside Tibet.

Monday, July 16, 2007

Palestinian Poet, Mahmoud Darwish, Reported in the NY TImes Today

Palestinain Poet, Mahmoud Darwish Blasts Infighting [NYTimes, AP, July 16,2007]

In Jerusalem

by Mahmoud Darwish

Translated by Fady Joudah

For a collection of audio poems in English and Arabic by Darwish click here.

For the same news article about Darwish's recent public appearance in Haifa, click here for Haaretz coverage in Israel.

GAZA CITY, Gaza Strip (AP) -- The world's most recognized Palestinian poet, Mahmoud Darwish, delivered a stinging tirade against Palestinian infighting on Sunday in his first public appearance in decades in the Israeli city of Haifa.

Click here to continue article.

In Jerusalem

by Mahmoud Darwish

Translated by Fady Joudah

In Jerusalem, and I mean within the ancient walls,

I walk from one epoch to another without a memory

to guide me. The prophets over there are sharing

the history of the holy . . . ascending to heaven

and returning less discouraged and melancholy, because love

and peace are holy and are coming to town.

I was walking down a slope and thinking to myself: How

do the narrators disagree over what light said about a stone?

Is it from a dimly lit stone that wars flare up?

(excerpt from poets.org) To view the entire poem click here.

For a collection of audio poems in English and Arabic by Darwish click here.

For the same news article about Darwish's recent public appearance in Haifa, click here for Haaretz coverage in Israel.

"Among the predominantly Arab-Israeli crowd that assembled to hear Darwish were Jews- some of whom didn't even speak Arabic and could not understand what was being said.If you can stomach it, the long list of hate comments following the article in Haaretz is quite an education in relentless bitterness and hatred.

Ilana Shahaf, who organizes an annual poetry festival in the Negev kibbutz of Sde Boker, said that she came to share in the Arab public's excitement. "I wanted to feel a stranger among the words. As I climbed up the stairs with the crowd, I felt really excited for them. After all, no Hebrew-speaking poet today can generate this kind of excitement," she explained."

Thursday, July 12, 2007

Smith College Tibetan Literary Arts Exhibition

The exhibition catalog may be purchased from the Shang Shung Institute of America located in Conway, MA. Write: will@shangshung.org for information. The catalog which was spopnsored in part by the SSI, includes a diverse collection of writings by leading scholars in the field.

Thursday, May 17, 2007

A Small Stone Casts Its Ripple: Women Poets of Tibet

The following essay by Jacqueline Gens is reprinted from the catalog of The Tibetan Literary Exhibit, Smith College, 2007 in honor of HHDL's visit on campus in May 2007. The essay was commissioned by the curator of the exhibit, Marit Cranmer to address women poets of Tibet. Smith is also my alma mater ('81).

Over the past fifty years, the Western world has been introduced to an ocean of Tibetan literature still unfolding its treasury of knowledge. New titles appear annually on both spiritual and secular topics as the first generation of translators have become seasoned mediators (and meditators) between this ancient legacy and contemporary interest. At the same time, many Tibetans have themselves been introduced to Western languages. Their writing continues to evolve with the emergence of contemporary literary genres both inside Tibet and in exile. Fresh perspectives on the scope of Tibetan literary arts will deepen with further acquisition, cataloguing, digital preservation and scholarly attention to ancient writings.

Among poets across time and space from antiquity to the present there is the unspoken hermetic tradition of art as a common quest for personal transformation via language, a journey more about unknowing in the contemplative sense than mere intellectual certainties. The universal appeal of poetrymind and its endless variations is no less apparent in Tibet than any other world culture. Sandwiched between the two great civilizations of India and China, Tibet’s literary contribution to humanity looms distinct—increasingly so, as contemporary scholars reevaluate Tibet’s indigenous origins and recast history according to the literary and archaeological record rather than political or doctrinal agenda.

An essential Western approach to versification favored by modern poets is categorized as phanopoeia (image), melapoeia (sound) and logopoeia (mind). Here, within the texts curated for this exhibit, we find abundant representation of this tripartite classification. In translation, representations of pure melapoeia may prove compromised without the original sonic elements of rhythm and assonance. However, this is mitigated by the understanding that in the original language where much of Tibetan verse was sung, there follows Louis Zukofsky’s diagram “upper limit music, lower limit speech.” The sheer exuberance of Tibet’s longstanding fascination with the nature of mind and the process of thinking itself, framed by the figurative language of the majestic Tibetan landscape alone, should place Tibetan literature on a par with other world literatures. It’s natural then that some Western poets have already looked to aspects of Tibetan poetry for inspiration (Ginsberg, diPrima, Waldman, Quasha, Giorno, LLLevi), where consciousness and phenomenal interconnectedness via spontaneous composition have become primary considerations of post modern literature with verse being the natural extension of the poet's thought via the medium of breath.

For millennia Tibetans have composed poetry found in folk song (glu) and drama (ach’e lhamo); verses of great antiquity discovered at Dunhaung (snyan rtsom); the Gesar of Ling epic (sgrung) tradition sung spontaneously in metered verse; mystic songs of spiritual experience associated with tantric rites and the works of numerous practitioners such as Milarepa and Shabkar and others well into the modern era (nyams mgur); elaborate compositions based on the intricate Kavya training in versification emanating from the monastic colleges (snyan ngag me long ma); the Terma tradition of writings rediscovered in the mindstreams of future revealers (gter ston pa); and a host of native oracular traditions. From the lowest social strata of unlettered folk to the hierarchical pinnacle of Tibetan society these works were sung, spoken and heralded through the streets, encampments, monasteries, charnel grounds, caves or, in some cases, whispered in secret from generation to generation between master and disciple. Remarkably, a huge number of these compositions manifested as text through the labor intensive printing technologies unchanged for centuries and survive into the present.

Yet the presence of Tibetan women’s literature remains dismally but a small stone in this gigantic edifice of oral and written material. As a poet looking to the tradition searching for female voices, there is a marked lack of historic individuals toward to turn. One might hope that some cave or private household library may still yield a cache of lost writings of a Mira Bai or Sappho, or even an ordinary woman, however fragmentary, as happened with the discovery twenty years ago of Tang dynasty poets thought to be lost forever, in the attic of a barn in Xi’an where it lay undisturbed for over a thousand years. As recently as the 1960’s during China’s cultural revolution, numerous texts throughout Tibet were hidden in caves or buried where they would not be disturbed. It is hard to believe that in such a sophisticated mind culture as Tibet there are so few women authors. Still, a small stone casts its ripple.

Whether the work of women simply did not exist due to illiteracy, social circumstance, or lack of encouragment, can only be surmised, More likely, their work was considered of less importance and therefore not recorded or saved out of an androcentric preference but nonetheless existed at least in limited forms. There is some evidence that in the translation from Sanskrit to Tibetan, the gender of some female tantric lineage holders was altered linguistically when they entered into the Tibetan canon. However, what can be acknowledged is that the feminine principle itself is highly regarded within the Tibetan literary tradition as a matrix for personal transformation to which untold numbers of men and women staked their personal journey for realization. In her groundbreaking book, Women of Wisdom, Tsultrim Allione recounts the lives of a number of female Tibetan adepts. One such yogini, A-yu Khadro Dorje Paldron told her life story to Choegyal Namkhai Norbu, who by his own admission, uncharacteristically for a Tibetan, recorded her story while still a young man. Her biography is a thorough account of the social milieu in which such training and practices were undertaken equally by both men and women outside the established monastic colleges. This particular female biography (nam thar) indicates a legacy of writings and spiritual songs left behind by A-yu Khadro upon her extraordinary death. Perhaps her work was lost in the chaos of mid-century diaspora and cultural ruination but nonetheless the mere mention of such writings as existing signals encouragement for future scholars.

It will be generations before the full impact of the possibility for identifying unknown works by Tibetan authors might reveal themselves: lost manuscripts or folios discovered and reassembled, the puzzle painstakingly put together, clues followed up on the names of disciples of famous masters and oral histories taken in remote locations. Perhaps what is lost or non-existent will never come to light. One thing we know for certain is that there are at least some women’s voices from Tibet’s past to consider. Given that the first female institutions of higher learning first occurred in America in the 19th century, it is simply a miracle that the 11th century Machig Lapdron, a renowned reader of the prajnaparamita texts in her own time, wrote volumes that were preserved, even brought back to India and whose liturgies are still practiced today in an unbroken lineage.

Machig Lapdron’s (1055-1143) lineage of Chod exemplifies the highly sophisticated understanding of the cornerstone of the Mahayana teachings on emptiness and the illusory belief in an ego. In Buddhist philosophy, the ‘conceit’ of ego is perceived as the ultimate demonic force and obstruction to liberation. Fully comprehending this view releases the practitioner into a field of compassion whereas the psychical/physical becomes a means to feed the illusory demons of the mind’s projections thus embracing rather than rejecting negative forces through repression. Eighth century, Yeshe Tsogyal, an earlier incarnation of Machig Lapdron, in her parting advice incants these words, “I have yet to find any ‘thing’ that truly exists.” On the other hand, Nangsa Obum, a contemporary of Machig Labdron and famous “delog” draws on the metaphor of weaving, a traditional women’s occupation, to illustrate the stages of the path to realization in a famous folk drama widely known throughout Tibet. Her song in many ways closely parallels the tradition of Terighati (songs of the nuns from the time of the Buddha) drawing on the immediacy of her domestic life. However slender, these representations are but ciphers in a larger cultural context.

An aspiring Tibetan language student once asked the late Tibetan master, Chogyam Trungpa (1939-1987); “What do you really need to learn Tibetan?” “A new mind.” Tibetan culture, in general, has something to tell us about how a civilization can manifest so much wisdom and compassion with so little material culture, how the primacy of personal liberation stands in stark contrast to our own preoccupation with material advancement. Tibetan literature expresses a culture infused with a passion about mind and it might be interesting, even profoundly useful, for us to consider what such a society might be like in terms of human development and to listen deeply to what they have to say. Applying a new mind in search and research of Tibet’s literary treasures may well yield a few surprises and voices awaiting our notice, including those of women.

(sources on request)

Image from the Rubin Collection, NY

Saturday, April 14, 2007

Allen Ginsberg's Last Three Days

This year I missed the April 4, 1997 10th Anniversary of Allen's death. Here's a link to Jonas Mekas' home movie.

Father Death Blues (Don't Grow Old, Part V)

Hey Father Death, I'm flying home

Hey poor man, you're all alone

Hey old daddy, I know where I'm going

Father Death, Don't cry any more

Mama's there, underneath the floor

Brother Death, please mind the store

Old Aunty Death Don't hide your bones

Old Uncle Death I hear your groans

O Sister Death how sweet your moans

O Children Deaths go breathe your breaths

Sobbing breasts'll ease your Deaths

Pain is gone, tears take the rest

Genius Death your art is done

Lover Death your body's gone

Father Death I'm coming home

Guru Death your words are true

Teacher Death I do thank you

For inspiring me to sing this Blues

Buddha Death, I wake with you

Dharma Death, your mind is new

Sangha Death, we'll work it through

Suffering is what was born

Ignorance made me forlorn

Tearful truths I cannot scorn

Father Breath once more farewell

Birth you gave was no thing ill

My heart is still, as time will tell.

Allen Ginsberg

Monday, February 19, 2007

Year of the Fire Pig

Greetings for Year of the Fire Pig

“...and long purples

That liberal shepherds give a grosser name,"

Hamlet, IV vii 170

What’s not to reconsider in grosser terms?

Disarrays— a casual display of hungers

unabated or stout limbs to follow long afternoons

in nothingness where we dally no where

to the larger world of perfections. or split hairs

of judgement. Let’s not forget that our design

is on the other side of civility--

Cracked open: a hue of fruit, its juice

rooting our place in the cosmos,

only to settle on the bud with a taste of eternity.

It’s the long purple we stroke into being:

Wild snouts aflame,

urgent FIRE PIGS

with noses to the ground

searching for the root.

Jacqueline Gens

Brattleboro, Vermont

February 19, 2007

Sunday, February 04, 2007

Stephen Warrren Curtis 1946-1996

This past month I spent 11 days at the Northfield campus of Mt. Hermon Northfield School where we held our annual winter residency for the New England College MFA Program in Poetry that I co-direct. Being in Northfield, MA after nearly 30 years brought back many memories. Little has changed since I went to high school there graduating in 1968. It seems that even the cracks in the road were the same. My first husband, Stephen Warren Curtis, was born and raised in Northfield. I recently came across a website (click on the title) with his art work that my brother, Will, forwarded to me. Being on that abandoned campus, one of our faculty called, a “Wuthering Heights” experience (Steven’s favorite book), brought me back to my late teens and how formative those years were.

This past month I spent 11 days at the Northfield campus of Mt. Hermon Northfield School where we held our annual winter residency for the New England College MFA Program in Poetry that I co-direct. Being in Northfield, MA after nearly 30 years brought back many memories. Little has changed since I went to high school there graduating in 1968. It seems that even the cracks in the road were the same. My first husband, Stephen Warren Curtis, was born and raised in Northfield. I recently came across a website (click on the title) with his art work that my brother, Will, forwarded to me. Being on that abandoned campus, one of our faculty called, a “Wuthering Heights” experience (Steven’s favorite book), brought me back to my late teens and how formative those years were.

I was married to Stephen Curtis from 1969-1971 or 1972 (legally until 1982).Here I am in a photo booth shot the year I met Steven looking a bit like Madame Blavatsky. All of the works on this website by Steven were executed during the time we lived together in Bernardston, Massachusetts which subsequently were incorporated into an offset pamphlet that Stephen created. For years I would find the pamphlet in odd places such as in a storefront window in Harvard Square. I recently heard from Clayton Campbell that when John D. Merriam (Stephen’s primary collector) died his collections went to the Wiggins collection in Boston.

Both my grandparents were visual artists by profession and so marrying an artist seemed an obvious choice. Stephen and I were very inexperienced in terms of relationship, so things were always on shaky ground. I was 19 and he was 24 when we married in April of 1969, Originally, I had just wanted to run off to Boston with him but my mother pressed us into getting married and moving in with her as she liked Stephen quite a bit. In the end, that proved counteractive to my own desires to leave home and get out into the world. On the other hand, things happen for a reason, and this period of my life, while extremely difficult, proved rich inwardly setting in motion the direction I’m still uncovering today at age 57, decades later.

Like many of his friends, what I most enjoyed about Stephen was his integrity and total dedication to his art, as well as his quirky sense of humor, I was not surprised when I heard that he was found dead sitting up in a chair with a book opened on his lap to Ingress, a lifetime influence of his. While we were married, a local doctor whom he had once consulted, Dr. Failla, told him he would be dead at the age of 54 of a heart attack unless he changed his diet and lifestyle. I had heard that he tried to do this in his later years but I doubt he ever made it to the gym. By nature he was sedentary and genetically probably disposed toward high cholesterol. His family was poor and he grew up on comfort foods from the get go, — primarily of the white kind—wonder bread, potatoes. On the other hand, it seems that he died peacefully gazing on his most beloved vision of perfection.

Like Stephen, I had gone to Pioneer Valley Regional High School

In Northfield, MA when my family moved to Bernardston, MA in my senior year. His class would have been about 4 or 5 years earlier than mine. Prior to then, we had lived in Southern California and New York City. Our cultural backgrounds were totally different—mine first generation, eastern European and French, Catholic—his, generations of New England hardscrabble.

But Stephen had his guardian angels growing up—mainly the lively St. Clair clan of 88 Main Street Northfield who shared their somewhat magical family life with him supporting his artistic talents throughout his youth. One of the few changes I found on Main Street in Northfield was that the old rambling mansion of 88 Main had been replaced by a modest housing unit. Many of Stephen’s works were inspired by his muse, Eva (who later married the artist, James Langlois), one of the beautiful St Clair sisters, who can be seen in some of the drawings featured on the website.

Nonetheless, we had a lot in common on the psychic level as both of us lived in the shadow of early childhood iconic influences and family dysfunctions (a word not much in use back then). Yet, both of us we able to discuss serious issues like sexual abuse and homosexuality, at a time when there was little public discourse happening about these rather taboo topics. That is another aspect of my relationship with Steven that I appreciated. From Stephen, I primarily learned to draw on this energy for artistic sustenance rather than rejecting it as shameful or an unwanted intrusion, He also introduced me to many writers although I was fairly well read by the time I had met him. While married to him, I read the entire works of Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, and Eric Neumann whose works enriched my interests in anthropology and comparative religion eventually bring me to Tibetan Buddhism. One present he gave me was the complete works of Ezra Pound. These authors probably came to him via Yglesias, a popular professor of comparative literature at Brandeis, about 10 years his senior and a great influence on Stephen intellectually and later for me too.

So in retrospect, I’m very happy that I married Stephen because through him I learned a lot about the creative process and the unfolding of my deeply intuitive nature that I had tried to suppress throughout my childhood. On the practical level, we kept very different schedules. He would work all night until about 5:00 AM in the morning while I would sleep. I supported him and my family to some extent by working the second shift at a plastics factory. Back in 1971, it was still possible to feed an entire family of six for a week on $25 worth of groceries. I earned about $60 a week. As my family tended to be somewhat bohemian, this worked well for a while but after some time I found the regiment of factory work boring and unfulfilling for me personally. But it never ceased to amaze me when I would check in to his studio the next day after he had gone to bed, that he had worked hours on rendering some small detail of a drawing to perfection whether of a head of romaine lettuce or some fantastical being not of this realm. Many of his works started up as murky sketches, messes really, that would become jewels of crystalline clarity through his use of plain graphite on paper.

Unlike Stephen and his circle of male artist friends (Jimmy-Joe Langlois, Mark Spencer, Clayton Campbell, his mentor Luis Yglesias), I had not gone to College, nor had anyone in my family. In the mid-seventies after Steven and I separated, I would return to school eventually earning my BA in classics from Smith which I attended from 1978-1981 as one of the first Ada Comstock Scholars—waitressing and bartending my way through school while hitch hiking to class from Packer Corners Farm where I then lived.

Following my graduation, I legally divorced Stephen who was living in Boston since I was planning to move to Boulder, Colorado to pursue my interests in Tibetan Buddhism and language at the Naropa Institute. By then we had little contact or shared interests although we usually stayed in touch by phone every couple of years. In 1998, while working on a conservation job at the state capital in Madison, Wisconsin, I tried to call Stephen. But his number was disconnected. I then left a message on Beatrice St. Clair’s phone asking about him. Beth Backman (nee St. Clair) kindly returned my phone call to let me know that Steven had died a couple of years before. I eventually visited her a few times to catch up on Stephen’s life.

A lot of my journey does not include Stephen as I went on to live a few years at Packer Corners Farm (Total Loss Farm, his then friend Luis dubbed it), an altogether other story, then on to Boulder for 7 years where I worked at Naropa Institute in the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, on to NYC for another five years to work for the poet, Allen Ginsberg, then back here to New England where I’ve been in Brattleboro, Vermont since 1995. For the past 25 years I’ve been a student of Tibetan Buddhism primarily of Chogyam Trungpa’s (1939-1987) Shambhala lineage and the Dzogchen lineage of Choegyal NamkhaiNorbu.

On a rare note of curiosity one day, the poet Allen Ginsberg once asked me when I visited him at Lenox Hospital (circa 1987 when he had his gall bladder removed) about my early influences. Across from his bed was a reproduction of the girl with a watering can by Degas. I flashed on living with Steven nearly two decades earlier where once I had made a collage out of the girl with a watering can by meticulously cutting out a picture of Bob Dylan’s head and superimposing it on the Degas image that hung in our dining room for years. At the moment, Allen was thrilled with a hugely lush bouquet delivered to his room he had just received from Dylan’s office. “I took the left hand road” I told Allen that day, ” and never regretted it”. “Me too” Allen said. The day I married Stephen was the day that I took that decisive turn in the road and it led me to where I wanted to go.

At the heart of Stephen’ s work and his colleagues in the school of mystical surrealism, is a plumbing for unconscious artifacts emerging into the light of ordinary consciousness. In Steven’s case, there was the paradisiacal return to childhood images found in the Northfield landscape lived in the shadows of Moody’s progressive edifices with its elegant landscape and raw from his family dynamics who worked as servants on the Moody estate for generations. As such, the circumstances of Steven’s birth and his pedigree provided the classic ingredients for a “wounding” into artistic presence. As a poet many of the writers I admire come from such backgrounds, growing up out of the swamp, the backwoods, the ruined portal of passage from the lowest social strata to the higher realms of a pure perception through their art.

Although Stephen’s mother, Leolyn Curtis, who had conceived him out of wedlock in the 1940’s always claimed to him that he was the son of her love interest, a prosperous local farmer who had many children, it was widely known within the town that Steven’s actual biological father was an eccentric painter who lived with his mother from one of Northfield’s leading patrician families. Apparently, not only did Steven inherit his father’s artistic talent he exhibited at an early age but his looks as well.

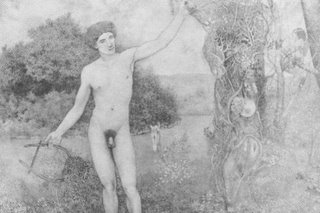

This mixed message considerably shaped his artistic vision in that his work explores the classic surreal ethos that things are not what they seem. Within the sometimes harsh and violent imagery of his work can be found a tenderness, the sadness of Eros or what William Carlos Williams came to call “Unworldly love that can not be satisfied. Like numerous artists before him, he circled this justification of art to make up for life’s impossible dilemmas that can be found in the arcane imagery of the Northfield chateau as a citadel of sanity and home to his erotic interests whether male, female or hermaphroditic who often appear in the guise of mythological figures.

Here is Apollo with his lyre lingering at the tree of Daphne transformed into a rich tangle of foliage, the real lovers embracing in the background in the Connecticut river, the entire scene transposed to Northfield, Apollo’s heart forever broken in unrequited love with an impossible yearning.

Here is Apollo with his lyre lingering at the tree of Daphne transformed into a rich tangle of foliage, the real lovers embracing in the background in the Connecticut river, the entire scene transposed to Northfield, Apollo’s heart forever broken in unrequited love with an impossible yearning.I don’t know much about Stephen’s life after the 1980’s except that he worked as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art where I’m sure he engaged in all sorts of conversations with aspiring artists.He was a great raconteur.

In many ways, Stephen’s lifetime achievement was his actual artistic process. It doesn’t matter that he did not become famous or ever have a major show although he certainly deserved some kind of show along with his colleagues. He lived the archetype of the quintessential artist forever beholden to his inner vision to render into worldly terms images that transcend into universal ciphers of tender unworldly love.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)